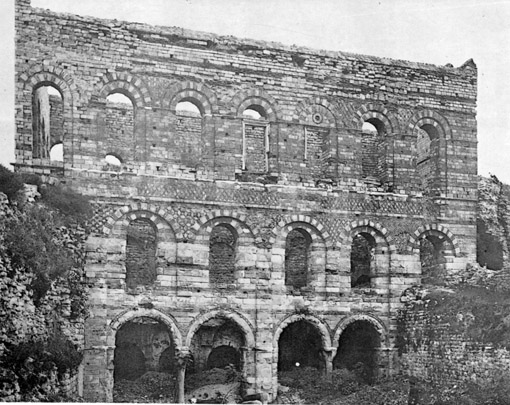

The now ruined three-story Byzantine Palace of Tekfur Saray is situated in the walls of the city and was an annex to the great Palace of Blachernai, a complex of buildings which stood further down the hill towards the Golden Horn. The palace was situated at the very highest point within the city walls and was visable overa wide area.

The Turkish name, Tekfur Saray, means "Palace of the Sovereign" from the Persian word meaning "Wearer of the Crown". It is the only well preserved example of Byzantine domestic architecture at Constantinople. The top story was a vast throne room. The facade was decorated with heraldic symbols of the Palaiologan Imperial dynasty and it was originally called the House of the Porphyrogennetos - which means "born in the Purple Chamber". It was built for Constantine, third son of Michael VIII and dates between 1261 and 1291.

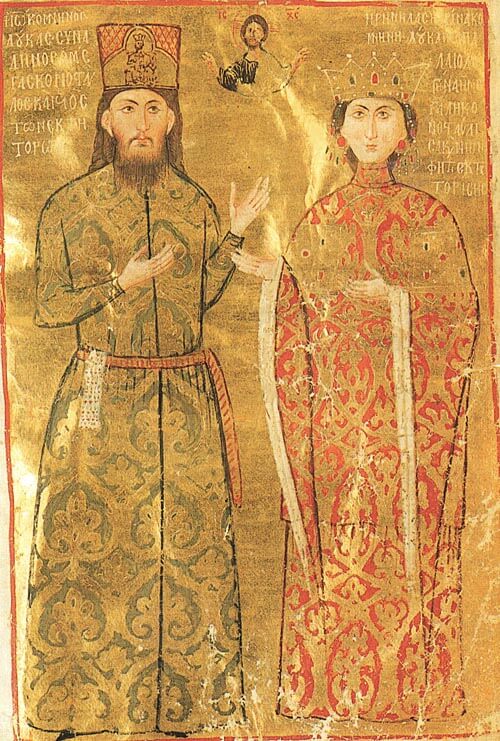

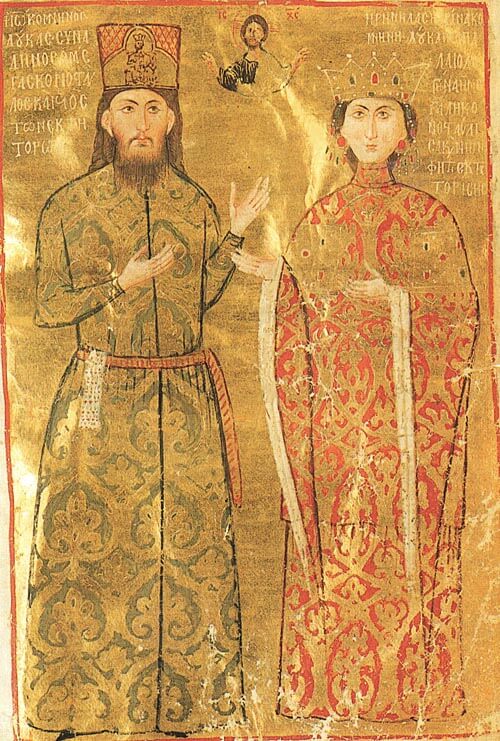

This is Constantine with his wife Eirene Raoulaina. Constantine was born in 1261 and died in 1306. This image was painted when he was in his thirties. He is wearing a tall red-silk hat - heavily embroidered with an enthroned image of his brother Andronicus, who was Emperor at the time, a caftan in heavy woven silk with tight sleeves, a red gold belt and an jeweled purse. Constantine wears his hair in long lanky, loose curls, crops his finely combed beard and it's obvious he has big ears. Small black shoes emerge from under his robe.

His wife is wearing a jeweled peaked crown from which are suspended ropes of pearls, gold and gemstones and large jeweled earrings. She wears a heavy red silk and gold robe. The top part descends to the knees with a fringe. Underneath is a matching dress in the same silk. The dress, which is lined in cream silk, has a high color and jeweled cuffs above the elbows, which are in heavy silk embroidery. Eirene's hair was been pulled back and falls in a long plait behind. Constantine and Eirene raise their hands in worship of Christ - who blesses them both.

This is everyday garb for them and this is how they would have dressed from day-to-day when they lived in the palace. At this time the silk could have been of Byzantine or Italian manufacture.

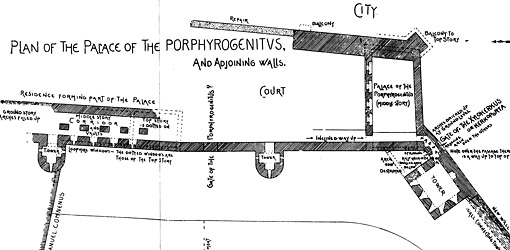

Their oblong palace was built between two wallswhich descend from the Porta Xylokerkou for a short distance, towards the Golden Horn. Its long sides, facing respectively north and South, are teransverse to the walls, while its short western and eastern sides rest, at the level of the second story, upon the summit of the walls. Its roof and upper floors have vanished. The whole surface of the building was decorated with beautiful patterns in brick and stone mosaic. The many windows of the palace are framed in marble and their were graceful balconies on the east and south, which looked out over the superb views the lofty position of the palace commanded.

There are two drawings of the palace. The first one by Cristoforo Buondelmonti is from around 1420. It shows the palace turned around and facing southwest. This was an artistic convention to make the building fit the map he had drawn. It is labeled "Palace of the Emperor". in this late period, during the last years of the Empire, the palace may have been the principal residence of the Emperor in this section of the city.

During the horrible civil wars of Andronicus III, and later John Catacuzene, the palace was occupied by both men at different times.

The palace was connected by a passage to the big Blachernai complex lower on the hill. It survives today because of its placement between two walls which insolated it from the terrible earthquakes which brought down so many other Byzantine palaces in the city.

This map was drawn by Melchior Lorck in 1559. he must have made detailed drawings of some of the most important buildings and a general view of the whole city panorama. He then made a detailed city view. He made mistakes in the final work. Here we can see our palace. He has turned the western facade, which faced out from the walls, around so that it faces the city. In the center of facade we can see the 'chapel' which projected out over corbels. It resembles the palace, but only in general terms. One can see how it dominated this section of the city.

Below is a reconstruction from Byzantium 1200 of how the palace might have looked in Byzantine Times.

During Ottoman times, the palace was used as used a menagerie by the Sultans. They had several around the city and one in Tukfur Saray housed two huge elephants, giraffes and other 'docile' creatures. One can see how the courtyard and ground floor could easily accomodate cages for animals as big as elephants and giraffes.

Here are two accounts from people who saw the Sultan's menagerie in the 16th century:

A man named Belon wrote, "There one saw the ruins of a very ancient palace, which the vulgates called the palace of Constantine. The Turks used it to feed their elephants and other docile beasts."

Monsieur d'Aramon. Ambassador of the French King, reported, "There was also a certain place where one saw a monstrous number of savage beasts which were well guarded and among theme were lions, lionesses, tamed wolves, wild wolves, wild cats, leopards, lynx, wild donkeys, and ostriches in quantity. In another place, one saw a certain beast which the residents called a sea pig and others called sea cow… In the same place they had two elephants, marvelously large."

A kiln was found at the site which was associated with a ceramic workshop that was established in the former palace in 1719. Later it became a glass factory. There were a large number of Jews living in this neighborhood at the time which was called Ayvansaray, and there were 7 synagoges here in 1900. They manufactured beautiful "Iznik" tiles in Tekfur Saray from the local white clay that had been used for hundreds of years to make pottery in and around Constantinople. In the 19th century Tekfur Saray was a community center for the Jews of this district and the poor of the comminity were housed here. After a second life as a bottle factory the palace was abandoned and finally burned in 1911.

It is hard to know exactly when the palace lost its peaked roof and wooden floors. From maps of the 18th century we can still see a roof, so when the place was 'ruined' - and what ruined meant at various stages - we don't know exactly. It's hard to image the firing of kilns within the old palace, although they could have been in the courtyard. I am trying to discover exactly where they were found.

Here in the two images at right you can see two Turkish maps from the 18th century that show Tekfur Saray in some detail.

Sorry for the terrible quality, it was really hard for me to pull this detail out of two low quality images.

In both cases you can see a balcony overlooking the city on the left and the peaked roof in place. The eves of the roof project out over the facade and gables. This conflicts with modern restorations of the palace. In the restoration above you can see a stepped gable with a shallow roof within. This must be wrong.

Looking again at these two maps, one of them actually has a view through the lower arches - you can actually see a bit inside.

The maps differ in that one shows the courtyard as straight, while the other is angled.

The second, angled one is true to plan, as we can see from Mamboury's drawing earlier in this article. The balcony over looking the city must have had wonderful views.

At the northwestern end of the court stood another part of the palace complex with huge windows piercing its western facade. The monogram of the Palaiologian dynasty was found here, but has vanished.

Visitors to the palace in Ottoman times reported seeing the double-headed eagle of the Palaiologi on a lintel and capitals carved with French lilies. This has been lost as well.

One scholar insists that these reports were inventions and that these decorations never existed. He contends that Tekfur Saray was built during the reign of Manuel Comnenus and Palaiologian symbols would never have been found in the fabric of the building.

My sources for this page were Byzantine Constantinople, the Walls of the city and Adjoining Historical Sites by Alexander Van Milligen, 1899, the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Volume 3, 1991 and and The Palace of Lausus and Nearby Monuments in Constantinople: A Topographical Study from the American Journal of Archaeology, volume 101, 1997, by Jonathan Bardill.

source http://www.pallasweb.com/deesis/tekfur-saray-blanchernai-byzantium.html

This is Constantine with his wife Eirene Raoulaina. Constantine was born in 1261 and died in 1306. This image was painted when he was in his thirties. He is wearing a tall red-silk hat - heavily embroidered with an enthroned image of his brother Andronicus, who was Emperor at the time, a caftan in heavy woven silk with tight sleeves, a red gold belt and an jeweled purse. Constantine wears his hair in long lanky, loose curls, crops his finely combed beard and it's obvious he has big ears. Small black shoes emerge from under his robe.

This is Constantine with his wife Eirene Raoulaina. Constantine was born in 1261 and died in 1306. This image was painted when he was in his thirties. He is wearing a tall red-silk hat - heavily embroidered with an enthroned image of his brother Andronicus, who was Emperor at the time, a caftan in heavy woven silk with tight sleeves, a red gold belt and an jeweled purse. Constantine wears his hair in long lanky, loose curls, crops his finely combed beard and it's obvious he has big ears. Small black shoes emerge from under his robe. There are two drawings of the palace. The first one by Cristoforo Buondelmonti is from around 1420. It shows the palace turned around and facing southwest. This was an artistic convention to make the building fit the map he had drawn. It is labeled "Palace of the Emperor". in this late period, during the last years of the Empire, the palace may have been the principal residence of the Emperor in this section of the city.

There are two drawings of the palace. The first one by Cristoforo Buondelmonti is from around 1420. It shows the palace turned around and facing southwest. This was an artistic convention to make the building fit the map he had drawn. It is labeled "Palace of the Emperor". in this late period, during the last years of the Empire, the palace may have been the principal residence of the Emperor in this section of the city. Below is a map of the palace, and surrounding structures.

Below is a map of the palace, and surrounding structures.

Below is a reconstruction from Byzantium 1200 of how the palace might have looked in Byzantine Times.

Below is a reconstruction from Byzantium 1200 of how the palace might have looked in Byzantine Times. During Ottoman times, the palace was used as used a menagerie by the Sultans. They had several around the city and one in Tukfur Saray housed two huge elephants, giraffes and other 'docile' creatures. One can see how the courtyard and ground floor could easily accomodate cages for animals as big as elephants and giraffes.

During Ottoman times, the palace was used as used a menagerie by the Sultans. They had several around the city and one in Tukfur Saray housed two huge elephants, giraffes and other 'docile' creatures. One can see how the courtyard and ground floor could easily accomodate cages for animals as big as elephants and giraffes. Here in the two images at right you can see two Turkish maps from the 18th century that show Tekfur Saray in some detail.

Here in the two images at right you can see two Turkish maps from the 18th century that show Tekfur Saray in some detail. The second, angled one is true to plan, as we can see from Mamboury's drawing earlier in this article. The balcony over looking the city must have had wonderful views.

The second, angled one is true to plan, as we can see from Mamboury's drawing earlier in this article. The balcony over looking the city must have had wonderful views.